Ballet Black – review

Linbury Studio theatre, London by Luke Jennings, The Observer,

Creating repertoire for a chamber ballet company is tricky. How do you ring the changes, given sparse resources and a mere handful of dancers? Ballet Black, now in their 11th year, have had successes and failures in this respect, but one choreographer who has consistently produced powerfully charged work for them is Martin Lawrance.

Lawrance’s background is in contemporary dance – he’s probably the most distinguished of Richard Alston’s choreographic disciples – and his work for the seven-strong company fiercely interrogates the classicism in which Ballet Black are grounded. Captured, a four-hander set to a taut string quartet by Shostakovich, deftly avoids structural cliche and leaves us wondering about the precise nature of the interactions between the two couples.

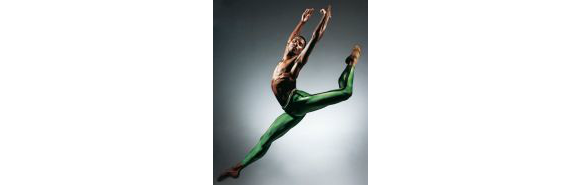

What you take away, first and foremost, is the rangy, staccato attack of Cira Robinson. Not for her the silken path. Instead, as she prepares to launch into a searching jeté or a string of posé turns to the scherzo’s shuddering cellos, you see the eyes widen and the nostrils flare. Like Nureyev, she sees no reason to make ballet look easy. Captured‘s best sequence starts as an adagio duet for Damien Johnson and Joseph Poulton. Lawrance runs the sequence just long enough to establish its intimate, meditative mood, and then in swings Robinson with quite another agenda and turns the thing on its head.

Ballet Black’s dancers work against the grain. The more you ask of them, the more you get. And neither Jonathan Watkins nor Jonathan Goddard asks enough. Together Alone sees Sarah Kundi and Jazmon Voss stalking each other to a pallid composition by Alex Baranowski. Watkins knows his onions, choreographically speaking, but all those slow-motion walks and meaningful stares don’t add up to much, and I found the soul-brother hip rolls a bit wince-making, in among the off-classicism. I know Alvin Ailey did this, back in the day, but that was then.

Goddard’s Running Silent is equally undemanding. A solo for apprentice dancer Kanika Carr, it seems to fall backwards in its determination to spare her serious technical challenge. Christopher Hampson’s Storyville, however, hits the spot with charm and exactitude. The piece, set to music by Kurt Weill, and borrowing elements of The Threepenny Opera, tells the story of country girl Nola (Robinson), and her rise and fall in a New Orleans dance hall. Robinson is fetchingly naive as the corn-pone, cotton-frocked Nola, and Kundi is balefully sexy as her nemesis, Lulu White.

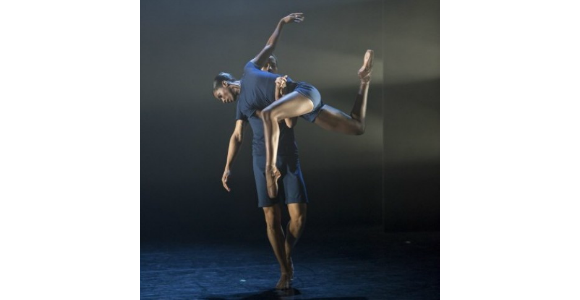

Weill’s music is something of a siren song to choreographers, and several have come to grief trying to turn his song cycles into dance. Hampson’s light touch enables him to avoid the ponderous fatalism of his predecessors, and there’s a nicely imagined sequence where Voss, as Mack the Knife, gives Robinson a diamond bracelet (shades of Kenneth MacMillan’s Manon), and then promenades her with a hand ruthlessly clamped to her throat. As in Manon, Nola dies as she’s lifted aloft by her lover (Johnson). Best, though, is the bittersweet enchantment of the opening and closing scenes, set to the haunting title song of Weill’s musical Lost in the Stars, based on Alan Paton’s novel of racial conflict and reconciliation, Cry the Beloved Country. Reminiscent in its simplicity of the choreography of Paul Taylor – the cast linked in a circle, hands aflutter – it’s both affecting and appropriate.